ew figures on Wall Street have demonstrated a sharper eye for systemic cracks in the global economy than Scott Bessent—and now, as Treasury Secretary, he is turning that same scrutiny on America’s mounting fiscal challenges.

Bessent comes to the Trump administration from the hedge fund Key Square Group, but earned his reputation while at Soros Fund Management. In 1992 Bessent predicted that Great Britain was likely to fall out of the European Monetary System (EMS).

The EMS relied on its member countries setting exchange rates in their local currencies to maintain balance across the 12 currencies in the system. Bessent noted that the British pound supported the entire U.K. mortgage industry and that the U.K. housing bubble had driven home prices to unsustainable levels. If the Bank of England raised rates to defend the pound, every mortgage in Great Britain would rise along with short rates.

Bessent’s predictions regarding the pound were spot on. After a brief struggle, the pound spiraled out of the EMS. Soro’s hedge fund made more than 40% on the trade.

Joining the Trump team has allowed Bessent to apply his brain power to the systemic problems the US has in funding its own debt. We will examine his proposed solution and the possibility it has of solving our fiscal problems.

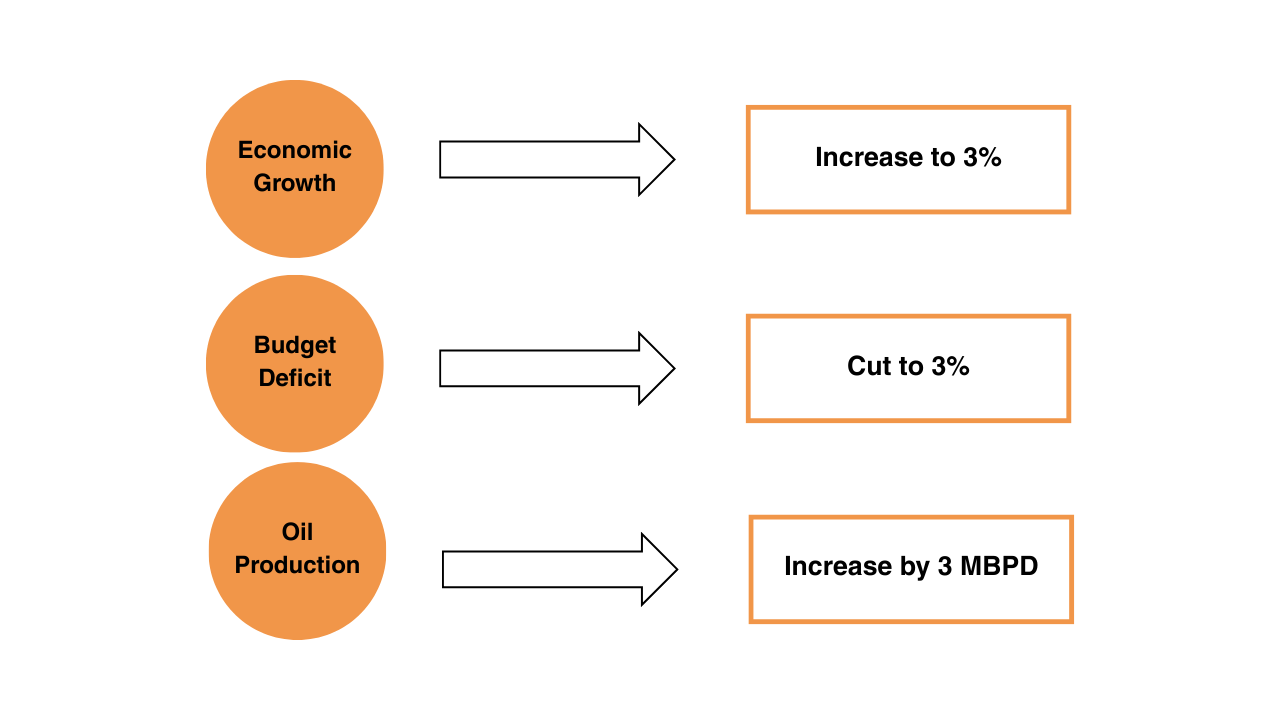

Bessent has crafted an economic package built upon what he refers to as the “Three 3s”.

Each one of these goals is a big stretch for the US. Doubling the rate of economic growth is far easier to talk about than to achieve. Cutting the country’s budget deficit by more than half would require either a major reprioritization of the county’s spending plans or the kind of revenue bonanza we last saw in the late 1990s (we posted our last budget surplus in 2000). And a 23% increase in oil production would set off all sorts of complaints from environmentalists and those who do not want the US to dominate global oil production.

Doubling the US rate of growth from 1.5% to 3.0% requires rekindling the growth that we last saw in the late 1990s. This would mean winning the current trade wars and stimulating major spending on artificial intelligence and other cutting-edge technologies.

Cutting the budget deficit is another play on winning the trade war. A country that runs a large trade deficit borrows money to fund its deficiency in funding economic growth. Increasing growth to a sustainable 3.0% means either increasing our budget deficit or cutting spending on nonessential items in the budget.

We did not need to win trade wars in the 1990s because our competitors were also our key strategic allies. Japan holds the most US debt by a foreign nation ($1.1T) and they have traditionally funded our deficits, but Japan is one of our closest allies. China is also a major debt holder ($860MM), although this is down from a peak of over $1.2B in 2013. China is not an ally of the US and its policies are not considered friendly to our long-term interests. China has paid down its US borrowing by largely diverting funds to its Belt and Road initiatives. With Belt and Road borrowing drying up, continued reliance on Chinese lending could expose the US to significant downside risks.

We need to reduce our borrowing from China, yet we are currently beholden to their dominance of rare earths and their control of major exports like clothing, pharmaceuticals, and home furnishings. President Trump has tried to address the large trade deficit the US has with China, but thus far he has not been successful. We can hope that future efforts will be more fruitful. In the meantime, we have to put a big question mark on this aspect of Bessent’s plan.

The final leg of Bessent’s three-legged stool is probably the easiest for the Trump team to pull off. Yes, there will be innumerable complaints from environmentalists and global warming activists about US oil dominance that President Trump will ignore. What Bessent needs to pull off this strategy is the Trump administration support which he will receive.

The Trump administration has placed a lot of bets on Bessent’s Three 3’s and the trade war is closely connected to it. Winning the war is necessary to produce a higher GDP and a lower budget deficit. We share the Trump administration’s confidence in generating ever bigger oil production but are less confident in the US’s ability to generate consistently higher economic growth and lower budget deficits.

The past decade has seen falling US borrowing from China as China diverted dollars to Belt and Road lending. China has cut back sharply on Belt and Road lending in the past year, and US borrowing from China has once again begun to rise.

The Trump administration initially aimed significant rhetorical and policy tools at China to dissuade them from continuing to run trade surpluses against the US. In recent months, President Trump has retreated from his sharp rhetoric and aggressive policy tools aimed at China. The policy tools China has aimed at the US, especially rare earth exports, have apparently convinced Trump to back down from his initial aggressive stance.

Absent a significant positive shift in our relationship with China, we see a small chance of a consistent acceleration in US economic growth and are similarly skeptical of a big improvement in the US’s budget deficit. China controls major export markets to the US, and we cannot accelerate growth or reduce borrowing without accelerating these key arms of the economy.

We can undoubtedly accelerate growth in the artificial intelligence space, but that growth is partially a function of China standing out of our way. A continued aggressive stance by China regarding artificial intelligence means a continued struggle to maintain a 3% rate of economic growth.

China is also turning back to its trade surplus with the US. The more China generates a trade surplus, the less the US will be able to reduce its overall borrowing needs. We doubt that the US will be able to cut its borrowing in half absent cooperation from China. We are discouraged about a revised Chinese approach toward the US, and therefore see faint odds that China will be collaborating in achieving the Three 3’s.

To summarize, we share the Trump administration’s confidence in driving US oil production to new highs. We are far more skeptical that China will cooperate in our efforts to lift our economic growth or reduce our borrowing needs. Absent help from China, we feel that the Three 3’s will come up short of our need to rebalance the US fiscal situation.

Given the structural trade challenges the US faces in trying to achieve the GDP growth of the Three 3s plan, our stance continues to be that the S&P 500 will produce modest 5% type returns as stated in our prior Strategic Insights Positioning Your Portfolio for a Trade War.